Managing toothwear

Direct composite resin as a minimally invasive restorative option for toothwear by Dr Marie Sanfey

While the precise incidence of non-carious tooth surface loss today is unknown, anecdotal reports suggest that toothwear is on the rise in the Irish population. Changes in the modern diet involving increased consumption of carbonated and alcoholic drinks and increasingly stressful lifestyle habits likely play a large role in this. The challenge of toothwear as a complex restorative issue is one that faces general practitioners on a daily basis.

Like any dental treatment plan, the first stage of interceptive treatment of toothwear is management of acute conditions, followed by prevention, stabilisation, definitive restoration, monitoring and maintenance. The scope of toothwear management in its entirety is obviously beyond the capacity of this short article, so I will focus on potential uses for direct composite in some or all of the aforementioned stages.

Acute management

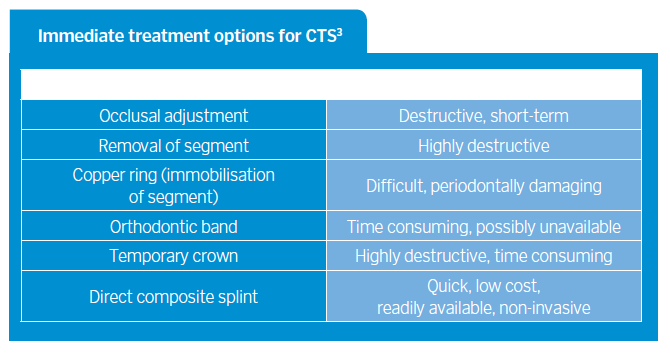

Direct composite resin can be used to treat acute conditions caused by toothwear such as Cracked Tooth Syndrome (CTS). CTS is often seen in patients who have evidence of anterior tooth surface loss which has resulted in absent or inadequate excursive guiding surfaces. The posterior teeth then fail to be discluded in functional movements and are often subject to undesirable lateral loading forces which can result in crack propagation1,2. CTS can be managed in several ways, including but not limited to the options listed in Table 1 (below).

It is generally acknowledged that the sooner a cracked tooth is appropriately addressed, the lower the risk of irreversible damage. The relative speed and ease of placement of a direct composite splint are appealing, along with its non-invasive nature. Following the principles of Dahl4, Banerji et al5 have explored the placement of composite bonded to the affected tooth in supraocclusion (excepting patients with limited eruptive potential) and observed encouraging results; resolution of symptoms and relative axial movement of the dento-alveolar segment culminating in re-establishment of contacts after a period of time.

This direct composite splint can be used as relief of acute symptoms but can also allow the practitioner to efficiently plan for the definitive restoration where interocclusal space may be limited, as is often the case in toothwear patients. Once contacts on adjacent teeth re-establish, the composite can be replaced by the definitive restoration without destructive reduction of natural tooth tissue. CTS treatment options with direct composite also include the placement of intra-coronal restorations; Opdam et al6 report alleviation of symptoms in 75 per cent of cases.

However, as CTS is often seen in patients displaying parafunction, it is worth noting that with repeated cycles of excessive force, the likelihood of failure of the adhesive layer is much higher without cuspal coverage. This naturally introduces the role of direct composite onlays in the management of CTS; these can be placed in supraocclusion as above or by reduction of the occlusal surface by 0.5-1mm. I will discuss this use of direct composite in further detail below.

Prevention and stabilisation

Direct composite can play a role in stabilising the patient’s occlusion and preventing further pathological wear. This doesn’t necessarily have to involve full mouth rehabilitation. In some cases, it may be as simple as placing a “canine rise” which restores the patient’s excursive guiding surface providing a mutually protective occlusal scheme.

A clinical example is demonstrated in Figures 1 and 2 where a patient was developing symptoms of CTS on his unrestored lower left first molar clearly as a result of undesirable lateral loading due to loss of canine/anterior guidance in functional excursions. By simple replacement of the worn tooth tissue with direct composite, the patient’s canine guidance was restored, which allowed disclusion of the posterior teeth on excursion. Immediately, the patient reported relief of symptoms. While not a guaranteed success and case selection is key, this can provide an efficient, non-invasive, cost-effective solution.

The decision to conform or re-organise the patient’s occlusion must be determined before any restorative treatment by analysing and planning on articulated study casts. The amount of interocclusal space available may influence the practitioner’s choice of material. However, with a large evidence base behind the use of direct composites applying the Dahl concept7,8 limited interocclusal space can be successfully managed in a minimally invasive manner.

- Laterotrusion before placement of a “canine rise” as discussed in ‘Prevention and stabilisation’ section

- Laterotrusion after placement of a “canine rise” as discussed in ‘Prevention and stabilisation’ section

- Pre-operative smile as part of aesthetic assessment

- Pre-operative smile as part of aesthetic assessment

- Fig 5 Pre-operative smile as part of aesthetic assessment

- Fig 6 Freehand intra-oral mock-up for aesthetic preview

Anterior direct composite restorations

Following similar logic, the placement of anterior restorations on worn teeth can serve not only as an aesthetic and functional restoration of the affected teeth but also as stabilisation of the patient’s occlusal disharmony, thus protecting posterior teeth also. When a large restoration is required anteriorly and reliable bonding is possible, the option exists to restore either directly or indirectly using either a class III/IV/V composite, direct composite veneer, indirect composite veneer or an indirect porcelain veneer.

In recent years, resin composites have improved by leaps and bounds, both in their physico-mechanical and aesthetic properties. A multitude of composite systems have been developed which follow biomimetic principles for optimum aesthetic emulation of the diverse biostructures within teeth. Figures 3-14 show a very rudimental example of what can be very easily applied clinically.

Using these materials for direct restorations can fulfil a patient’s request for a “smile makeover” in a relatively cheap, non-invasive/minimally invasive, reversible manner and can be carried out without anaesthetic in a single visit. Naturally, this treatment modality is gaining huge popularity with dentists and patients alike and has become synonymous with certain aspects of contemporary dental practice, “bleach and bond” is a common phrase used. That is not to say that indirect veneers are obsolete.

Composite veneers do carry disadvantages: they are extremely technique sensitive and time-consuming, they require extensive polishing to achieve high lustre and even then this will fade with time, they are prone to staining and chipping and require more maintenance. The longevity of composite veneers is estimated at approximately eight to 10 years when compared with approximately 15-20 years for porcelain veneers9.

Some dentists look upon composite veneers as an ideal “transitional bonding” which allows minor or major occlusal and aesthetic changes to be made in a reversible and easily adjustable way, which can then be converted to more highly aesthetic porcelain veneers in the longer term.

This is intelligent amalgamation of direct and indirect restorations and to me is consistent with the concept of contemporary management of toothwear. I certainly believe no one technique or material for veneers is correct or incorrect; as long as ultra-conservative principles are followed and materials are used appropriately with respect for their limitations, successful outcomes can be achieved.

Posterior direct composite restorations

Where a large restoration is required in posterior teeth and bonding is possible, there is an option to restore either directly or indirectly using inlays or onlays. Looking firstly at inlays, research has shown that there is no advantage of indirect inlays over well-placed direct restorations, mainly due to the high stresses generated by a “wedging” force laterally on the buccal and lingual walls10. If a direct restoration is not desired by the patient or dentist, a way of overcoming this disadvantage is to convert the inlay design to an onlay design including cuspal coverage, creating more favourable distribution of stresses following biomimetic principles.

Once the decision is made to restore the tooth with an onlay, there is still a choice of direct or indirect. Direct onlays can be placed with resin composite to good effectıı. While there are drawbacks of being highly technique sensitive and time-consuming, there are benefits of a single visit, low cost, no need for removal of undercuts and improved bonding as the dentin is freshly cut and uncontaminated. Alternatively, indirect composite onlays can be considered.

Advantages include higher polymerisation conversion due to “post-light-cure”, reduced polymerisation contraction due to extra-oral curing, ease of accuracy with proximal contacts and occlusal prescription. Disadvantages include two-stage process, higher cost due to lab fee, issue of contaminated bonding substrate while temporised.

There has been debate whether indirect composite onlays are actually superior. Van Djiken et al12 and Wassell et al13 report no significant superiority over 11 years and five years respectively. This may be partly due to a “weak link” in the resin cement interface. Some practitioners aim to overcome this by using pre-heated conventional composite in place of resin cement.

A study in Norway in 2014 reported there is “no high quality evidence that supports or rejects the practice of placing an indirect restoration on a heavily restored vital molar rather than a direct restoration to ensure longer tooth survival”14. While composite onlays offer an aesthetic tooth-coloured option for restoring posterior teeth, there are still problems with the amount of tooth reduction required (2mm) and wear resistance.

Naturally, the alternatives of indirect adhesive onlays made of either ceramic or ideally gold can also be considered in the long-term restoration of worn posterior teeth. At the very least, direct composite onlays can be seen as a gateway to these restorations once a patient has shown tolerance of a new occlusion.

- Mounted casts in centric relation on a semi-adjustable articulator

- Fig 9 Putty template from intra-oral mock-up to aid diagnostic wax-up

- Fig 10 Diagnostic wax-up with occlusal scheme incorporated into palatal contours

- Fig 11 Putty template from diagnostic wax-up to aid direct placement of composite veneers with rubber dam

- Fig 12 Biomimetic layering approach to composite veneers

- Fig 13 Post-operative smile

- Fig 14 Post-operative intra-oral

Monitoring and maintenance

As mentioned above, the longevity of direct composite does mean that this treatment modality must be looked at as more of a medium-term restorative solution for most toothwear patients. Failure can occur in the form of marginal leakage, staining, loss of surface lustre or worse, bulk fracture. The risk of bulk fracture is naturally significantly higher in parafunctioning patients. The use of a Michigan splint post-operatively can be recommended in patients with bruxist habits.

Conclusion

Looking at toothwear cases, a recent systematic review has stated “there is no strong evidence to suggest any material is better than another. Direct or indirect materials may be feasible options to restore severely worn teeth”15. This would beg the question how destructive indirect restorations can be justified as a treatment of already structurally compromised teeth, when a less invasive alternative with direct composite has good success rates16, 17.

Traditionally, adhesion wasn’t as reliable and so conventional crowns were favoured for restoring lost clinical crown height. With reliable modern adhesion and composites, it is rare to need to resort to this technique which is of high financial and biological cost.

About the author

Marie graduated as a dentist from University College Cork in 2012. She moved to London where she worked for three years in Kent and Westminster. During this time, she completed many training courses and successfully completed her MJDF exams at the Royal College of Surgeons, England.

She has been awarded Distinctions in her Certificate and Diploma in Aesthetic Restorative Dentistry in King’s College London and has decided to continue the same in a Masters programme. Upon returning to Ireland, Marie worked in a number of practices in Cork before making the move to Dublin where she now works in the Seapoint Clinic. Marie’s main interests involve minimally invasive restorative techniques, smile design, patient education and treating children.

References

- Davies SJ, Murray RWJ, A Guide to Clinical Occlusion, British Dental Association 2002

- Davies SJ, Gray R, Whitehead S, Good Occlusal Practice in Advanced Restorative Dentistry, British Dental Journal 2001;198;421-434

- Banerji S, Mehta SB, MIllar BJ, Cracked Tooth Syndrome Part 2: Restorative options for the management of Cracked Tooth Syndrome 2010;208;503-514

- Poyser NJ, Porter NWJ, Briggs A, Chana HS, Kelleher MGD, The Dahl Concept: the Past, Present and Future, British Dental Journal 2005;198;669-676

- Banerji S, Mehta SB, MIllar BJ, Cracked Tooth Syndrome Part 2: Restorative options for the management of Cracked Tooth Syndrome 2010;208;503-514

- Opdam NJ, Roeters JJ, Loomans RA, Bronkhorst E, Seven year clinical evaluation of painful cracked teeth restored with a direct composite restoration, J Endod 2008;34:808-811

- Chu FC, Siu AS, Newsome PR, Chow TW, Smales RJ, Restorative management of the worn dentition series, Dental Update 2009;29.

- Gulamali AB, Hemmings KW, Tredwin CJ, Petriethe A, Survival analysis of composite Dahl restorations provided to manage localised anterior toothwear: a 10 year follow-up, British Dental Journal 2011;211;E9

- Emanuel Layliev, Jeff Golub-Evans Direct Veneers (Chapter 15) and Porcelain Veneers (Chapter 16), Contemporary Esthetic Dentistry book

- Fisher DW, Caputo AA, Shillingburg DDS. Photoelastic analysis of inlay and onlay preparations. J Prosthet Dent 1975; 33: 4753

- Neel Panchal, Shamir B Mehta, Subir Banerji and Brian J Millar, Aesthetic Resin Onlay Restorations:‘Rationale and Methods’, Dent Update 2011; 38: 535–546

- Van Dijken JW. Direct resin composite inlays/onlays. An 11-year follow-up. J Dentistry 2000; 28(5): 299–306

- Wassell RW, Walls AW, McCabe JF. Direct composite inlays versus conventional composite restorations: 5 year follow up. J Dentistry 2000; 28(6): 375–382

- T Laegreid, NR Gjerdet, A Johansson, A-K Johansson, Clinical Decision Making on Extensive Molar Restorations, Operative Dentistry, 2014, 39-6, E231-E240

- ME Mesko, et al., Rehabilitation of severely worn teeth: A systematic review, Journal of Dentistry (2016)

- AB Gulamali, KW Hemmings, CJ Tredwin, A Petriethe, Survival analysis of composite Dahl restorations provided to manage localised anterior tooth wear (ten year follow-up), BDJ 2011;211;E9

- KE Ahmed and S Murbay, Survival rates of anterior composites in managing tooth wear: systematic review, Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 2016 43; 145–153

Tags: Alcoholic Drinks, Carbonated drinks, Cracked Tooth Syndrome, CTS, Dr Marie Sanfey, IDM, Ireland's Dental magazine, Irish Population, Jan 2017, January 2017, managing toothwear, toothwear

You must be logged in to post a comment.