The risk of anti-fungal resistance in dentistry: lessons from a Japanese fungus

[ Alex Farrow-Hamblene ]

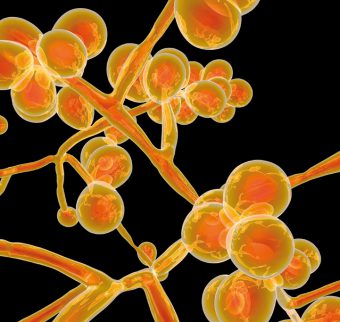

Globally since 2009, Candida auris, a fungal species closely related to Candida albicans, has been responsible for a number of drug-resistant hospital-acquired fungal infections. Though C. auris is yet to be isolated from the human oral microbiome, ten years since its discovery in Japan, what can the UK dental profession learn about antimicrobial stewardship and the prescription of anti-fungal agents from this lesser-known ‘superbug’?

Over my last four years as a dental student, the importance of antimicrobial stewardship and best practise when prescribing antimicrobial agents has been a key focus of my clinical training. Where antimicrobial resistance remains a growing threat to public health in the UK1, the Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme’s (SDCEP) clinical guidance document: Drug Prescribing for Dentistry2, is a valuable resource to General Dental Practitioners (GDPs) in protecting against the indiscriminate use of antibiotics in Primary Dental Care. Despite this guidance – and the fact that the overprescription of broad-spectrum antibiotics can lead to a reduction in therapeutic inefficacy3 – the similar threat of anti-fungal drug resistance in dentistry is less reported within dental literature.

Amongst the many microbial species that colonise the oral cavity, Candida albicans is the most common of the fungal species4. Though often co-existing as a harmless commensal microbe, acute and chronic episodes of immunosuppression can lead to candida overgrowth and symptoms of opportunistic oral or systemic candidiasisv. In such cases, GDPs may quickly reach for the prescription pad, prescribing an anti-fungal agent such as the polyene nystatin (oral use) or the azoles miconazole (topical use) or fluconazole (oral & systemic use)5. However, the overuse of antifungal agents, like antibiotics, can similarly confer multi-drug resistance6,7. As resistant strains of Candida can have an adverse effects on respiratory and gastrointestinal health upon colonisation of their respective epithelia8, 9, 10, could drug-resistant strains of Candida, such as C. auris, pose a threat to the health of susceptible patients in general dental practice?

To date, Candida auris is yet to be established as part the human oral microbiome, first isolated from the ear of an elderly patient in Tokyo Metropolitan Geriatric Hospital (Japan) in 200911,12. A close derivative of Candida albicans, in the ten years since its discovery, C. auris has been identified as a global cause of numerous life-threatening cases of fungaemia in hospital-bound patients11, 12; the strain also linked to several hospital infections in the UK13. Interestingly, as the overuse of azole antifungals in the East Asian agricultural industry and global medical setting have been cited as a likely reason for the ‘success’ of this multi-drug resistant fungus11,12, similar resistant fungal strains may also develop if anti-fungal agents are overprescribed, or used prophylactically, in dentistry; particularly as the use of azoles in the UK, two of the three licensed anti-fungals in the Dental Practitioners’ Formulary5, appear to have grown over recent years14.

So, what lessons can the dental profession learn from the emergence of C. auris as a nosocomial (hospital-acquired) infections in recent years? Firstly, ensuring that clinical audit, addressing the appropriateness of antimicrobial prescribing, includes antifungals as well as antibiotics should be encouraged; assessing how local prescribing habits match SDCEP guidance2 in the hope of identifying and minimising anti-fungal overprescription. Similarly, as advocated when treating oral bacterial infections, local measures should always be considered before prescribing any antimicrobial agent. For example, as described by SDCEP2, in the case of the candidal infection denture stomatitis, establishing the likely cause of fungal overgrowth and remedying this, e.g. educating patients in the improvement of denture hygiene, should be a first-line approach when managing oral fungal infections.

Arguably, the suggestions above should already form part of everyday clinical practice. However, a difficulty faced in promoting antimicrobial stewardship within NHS Dentistry is ensuring that GDPs are best placed to make such changes, i.e. have access to necessary tools and funds to implement recommendations. For example, the National Institute of Clinical Healthcare Excellence’s (NICE) guidance [NG15]: Antimicrobial stewardship: systems and processes for effective antimicrobial medicine15, suggests that in the case of persistent antimicrobial infections, oral microbiological sampling techniques should be encouraged to improve the specificity of diagnoses and thus the appropriateness of an antimicrobial prescription. Though an example of active antimicrobial stewardship that could be useful in identifying drug-resistant fungal strains, the likely costs, need for additional training, the lag time between diagnosis and prescription and the storage and transport of microbiological samples to and from a clinical laboratory are potential barriers to such a programme.

In the meantime, it seems prudent that dental advisory committees and dental schools should continue to advocate best prescription practice, emphasising the more inclusive term of ‘antimicrobial resistance’ over ‘antibiotic resistance’ in guidance documents and teaching; ensuring that GDPs and students are well aware that all modes of antimicrobial agents, available for prescription, are sensitive to drug resistance. Although available for free, increasing the ‘appeal’ of NICE’s antimicrobial prescribing guidance15 may be of benefit in increasing both readership and compliance with such guidance.

It is also an opportunity for verifiable CPD, which is especially important as antimicrobial prescribing is not yet recognised by the General Dental Council (GDC) as one of their ‘highly recommended CPD topics’17.It may also lead to making such information more ‘user-friendly’ as part of an app or interactive resource for GDPs, the latter pioneered by SDCEP2 and the Scottish Antimicrobial Prescribing Group (SAPG)16.

Ten years on from the first case of a C. auris infection in Japan, the exact threat of this drug-resistant fungus in primary care dentistry remains unknown. However, where the spread of anti-fungal resistance poses a tangible threat to dental and general public health, it is hoped that this article emphasises the importance of evidence-based and appropriate anti-fungal prescriptions, acknowledging that if the UK wants to remain at the forefront of dental antimicrobial stewardship, improving the ease at which the recommendations from clinical guidance documents can be implemented in primary care by UK-based GDPs is a key, and timely, next step.

References

- Public Health England. Antimicrobial Resistance. Online information available here. (accessed 17 August 2019).

- Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme. Drug Prescribing for Dentistry Dental Clinical Guidance – Third Edition. Dundee: NHS Education for Scotland. 2016. ISBN: 978-1-905829-28-6.

- World Health Organisation. Antibiotic Resistance. Online information available here. (accessed 17 August 2019).

- Akpan A, Morgan R. Oral candidiasis. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 2002. 78: 455-459.

- National Institute of Health Care Excellence. Dental Practitioners’ Formulary: List of dental preparations. Online information available here. (accessed 17 August 2019).

- Tumbarello M, Tacconelli E, Caldarola G, Morace G, Cauda R & Ortona L. Fluconazole resistant oral candidiasis in HIV-infected patients. Oral diseases. 1997. 3: 110-120.

- Niimi M, Firth NA & Cannon RD. Antifungal drug resistance of oral fungi. Odontology. 2010. 1: 15-25.

- De Pascale G & Antonelli M. Candida colonization of respiratory tract: to treat or not to treat, will we ever get an answer? Intensive Care Medicine. 2014. 40: 1381-1384.

- Yousef S, Perry J & Shah D. Risk factors for candida blood stream infection in medical ICU and role of colonization – A retrospective study. Isolated Candida infection of the lung. Respiratory Medicine Case Report. 2015. 16: 18-19.

- Kumamoto CA. Inflammation and gastrointestinal Candida colonization. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2011. 14: 386-391.

- Casadevall A, Dimitrios P & Kontoyiannis VR. On the Emergence of Candida auris: Climate Change, Azoles, Swamps, and Birds. American Society for Microbiology: mBIO. 2019. 10.

- Lone SA & Ahmad A. Candida auris – the growing menace to global health. Mycoses. 2019. 62: 620-637.

- Public Health England. Candida auris – a guide for patients and visitors. Online information available here. (accessed 18 August 2019).

- Oliver RJ, Dhaliwal HS, Theaker ED & Pemberton MN. Patterns of antifungal prescribing in general dental practice. British Dental Journal. 2004. 196: 701-703.

- National Institute of Health Care Excellence Antimicrobial stewardship: systems and processes for effective antimicrobial medicine use [NG15]. 2015. Online information available here. (accessed 18 August 2019).

- Scottish Antimicrobial Prescribing Group. Antimicrobial companion app. Online information available here. (accessed 18 August 2019).

- General Dental Council. Recommended CPD topics. Online information available here. (accessed 18 August 2019).

Useful resources

- Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness programme – Drug Prescribing for Dentistry Dental Clinical Guidance app. Download here.

- Scottish Antimicrobial Prescribing Group – Antimicrobial companion app. Download here.

- National Institute of Health Care Excellence Antimicrobial stewardship: systems and processes for effective antimicrobial medicine use (2015).

About the author

Alex Farrow-Hamblen is a final year student at Carlisle Dental Education Centre / School of Medicine & Dentistry, University of Central Lancashire.

Tags: anti-fungal, Candida Albicans, clinical, japanese fungus